Posts in Autism Series

- Are Autistic Kids Being Over-diagnosed in the U.S. System?

- Could Rising Autism Rates Spark an Epidemic Among Kids?

- Stereotypes of Autistic Kids: Beyond the Myths (This post)

- Is It Autism? Symptom Overlap in Mild Cases

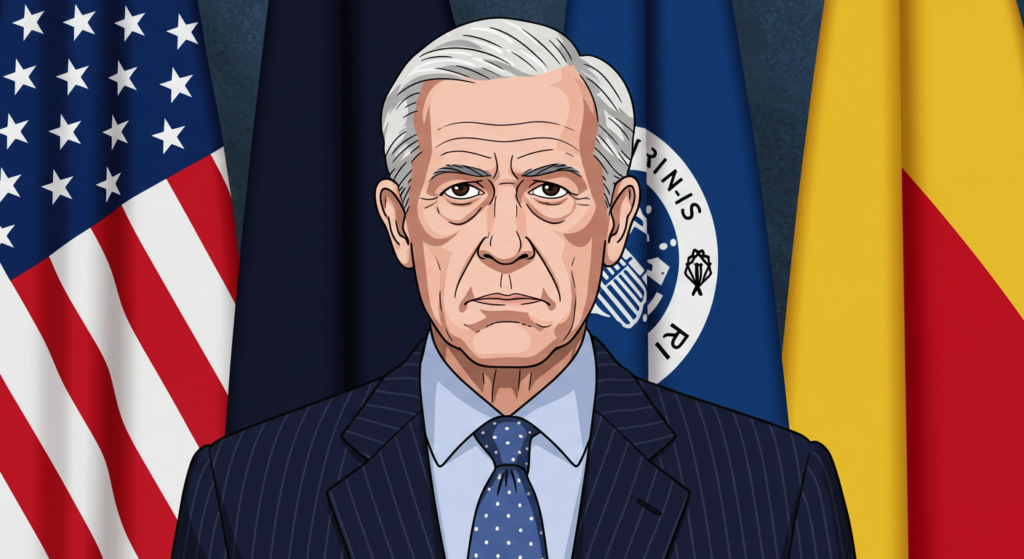

These are kids who will never pay taxes, they’ll never hold a job, they’ll never play baseball, they’ll never write a poem, they’ll never go on a date, many of them will never use a toilet unassisted.

By Robert F. Kennedy Jr., U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary, April 2025

After backlash, he clarified on Fox News that he meant the ~1 in 4 autistic children with “severe autism”.

To me, Kennedy’s words suggest he sees only severe cases as “truly” autistic, dismissing milder ones.

I’ve had similar thoughts.

When I chat smoothly with someone, I’m shocked if they later say they’re autistic—their mild symptoms don’t match my mental image of autism. These misconceptions stem from stereotypes about autistic kids, shaped by daily life and movies.

Let’s explore these myths, define autism’s severity levels, and rethink what autism means.

Kennedy’s View: Is Autism Only “Severe”?

Kennedy’s April 16, 2025, press conference painted a grim picture: autistic kids as unable to work, create, or live independently. His clarification—that he meant the 27% with “profound autism” (nonverbal, minimally verbal, or IQ <50)—reveals a narrow view.

In his mind, autism seems to equal severe disability (Level 3), ignoring milder cases (Levels 1-2). This mirrors a common stereotype: autism is only “real” when it’s obvious or debilitating.

But autism is a spectrum, and Kennedy’s words risk stigmatizing all autistic kids by focusing on the extreme.

My Own Misconception

I get where Kennedy’s coming from. I’ve talked with people—kids or adults—who seem “normal” in fluent, natural conversation. When they mention an autism diagnosis, I’m surprised. Their mild symptoms, like slight social awkwardness, don’t scream “autism” to me.

I used to think autism meant severe challenges, like being nonverbal or socially withdrawn.

My view, like Kennedy’s, was shaped by stereotypes that overlook the spectrum’s diversity. This raises a question: what does autism really look like?

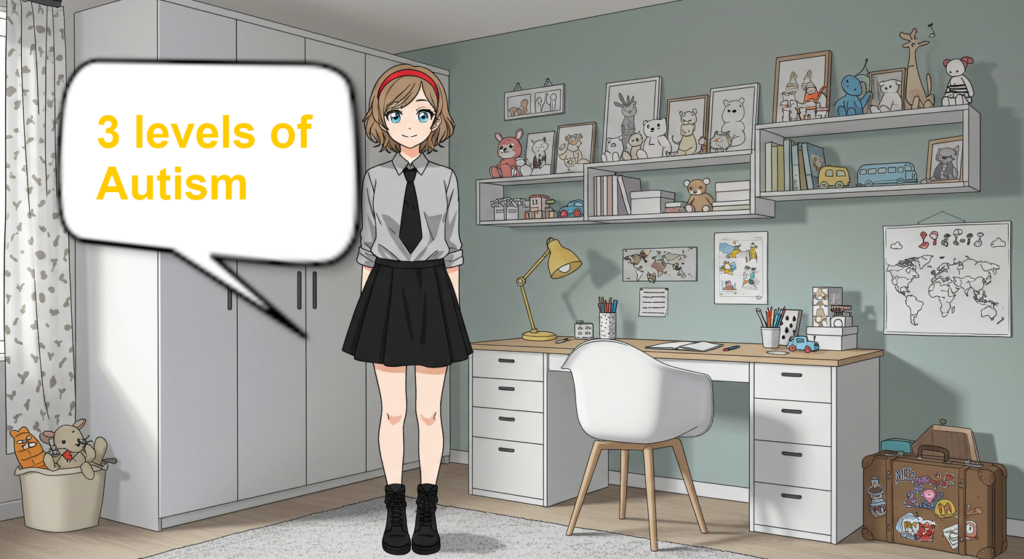

Defining Autism’s Severity Levels

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), per the DSM-5, involves challenges in social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors, with three severity levels based on support needs:

- Level 1: Requiring Support

Mild difficulties in social interactions (e.g., trouble starting conversations) and some inflexible behaviors (e.g., rigid routines). Kids might excel academically but struggle with social cues, often blending in. Example: A teen who chats fluently but avoids eye contact. - Level 2: Requiring Substantial Support

More noticeable social deficits (e.g., limited speech, odd responses) and frequent repetitive behaviors (e.g., hand-flapping) that disrupt daily life. Kids need structured support. Example: A child with short sentences and intense interests, needing classroom aids. - Level 3: Requiring Very Substantial Support

Severe social and communication challenges (e.g., nonverbal or minimal speech) and extreme behaviors (e.g., constant rituals) limiting function. Kids need full-time care. Example: A nonverbal child with sensory meltdowns, unable to live independently.

These levels show autism’s range, from subtle to severe. Kennedy’s focus on Level 3 ignores the 73% of autistic kids (Levels 1-2) who may function well, as I’ve seen in conversations.

Stereotypes in Daily Life

In schools, playgrounds, or stores, stereotypes about autistic kids create false expectations, making milder cases hard to recognize.

- Nonverbal and Helpless

People assume autistic kids can’t speak or learn, needing constant care. Example: A teacher expects an autistic student to be nonverbal and disruptive, surprised when they read fluently. Reality: Only ~27% are profoundly autistic (CDC 2023); many speak and thrive with support. This stereotype, like Kennedy’s, misses Level 1-2 kids who seem “typical.” - Socially Aloof

Autistic kids are seen as uninterested in friends, always alone. Example: A parent thinks an autistic child at a party is “in their own world,” not seeing their shy attempts to join. Reality: Many Level 1 kids crave connection but struggle with cues, appearing normal in casual chats, as I’ve experienced. - Disruptive Meltdowns

People expect autistic kids to have frequent tantrums. Example: A shopper assumes a child’s outburst is “bad behavior,” not sensory overload. Reality: Meltdowns vary; Level 1 kids might stay calm or withdraw quietly, defying this myth.

Stereotypes in Movies

Movies often exaggerate autism, showing either tragic disability or genius talents, shaping views like Kennedy’s and mine.

- The Savant Genius

Autistic kids are depicted as super smart in one area, like math or music. Example: In Rain Man (1988), Raymond has incredible memory but severe deficits, cementing this trope. Reality: Only 10-30% of autistic people have savant skills (Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2011). Most have average abilities, and Level 1 kids might just have strong hobbies, not genius. - The Tragic Burden

Autistic kids are shown as helpless, straining families. Example: In Mercury Rising (1998), Simon is vulnerable and nonverbal, needing constant protection. Reality: Many autistic kids (Levels 1-2) live fulfilling lives with support, and families adapt. This trope echoes Kennedy’s “destroys families” claim, ignoring milder cases. - The Quirky Oddball

Autistic characters are eccentric geniuses, socially awkward but funny. Example: In The Big Bang Theory, Sheldon’s implied autism involves rigid routines and physics brilliance, played for laughs. Reality: Quirks vary, and many autistic kids blend in, especially if mildly affected or over-diagnosed, as my blog on over-diagnosis notes (e.g., 30% re-diagnosis rate, Blumberg et al., 2016).

Breaking the Stereotypes

Stereotypes like Kennedy’s severe disability or movie savants distort autism’s reality. They make it hard to recognize Level 1-2 kids, who might seem “normal” in daily life, as I’ve seen. My blog on over-diagnosis (U.S. 3.2% vs. global 1%, Talantseva et al., 2023) suggests some mild diagnoses might be stretched, further blurring perceptions. We need education to see autism’s spectrum, from severe to subtle, without myths.

What autism stereotypes have you noticed? Let’s embrace neurodiversity and support every autistic child.

References

Blumberg, S. J., Zablotsky, B., Avila, R. M., Colpe, L. J., Pringle, B. A., & Kogan, M. D. (2016). Diagnosis lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 20(7), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315607724

Greenlee, J. L., Mosley, A. S., Shui, A. M., Veenstra-VanderWeele, J., & Gotham, K. O. (2016). Medical and Behavioral Correlates of Depression History in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 137 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S105–S114. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851I

Talantseva, O. I., Romanova, R. S., Shurdova, E. M., Dolgorukova, T. A., Sologub, P. S., Titova, O. S., Kleeva, D. F., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2023). The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1071181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1071181

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696

Pingback: Is It Autism? Symptom Overlap in Mild Cases -

Pingback: Could Rising Autism Rates Spark an Epidemic Among Kids?