Posts in Autism Series

- Are Autistic Kids Being Over-diagnosed in the U.S. System?

- Could Rising Autism Rates Spark an Epidemic Among Kids?

- Stereotypes of Autistic Kids: Beyond the Myths

- Is It Autism? Symptom Overlap in Mild Cases (This Post)

When a child is diagnosed with autism, it feels like a clear answer.

But what if it’s not?

Studies show 10-30% of kids initially labeled with mild autism (Level 1) are later re-diagnosed with something else, like a language disorder or ADHD (Blumberg et al., 2016).

Why does this happen?

Autism’s symptoms, especially in milder cases (Levels 1 and 2), often overlap with other conditions, leading to misdiagnoses. This confusion fuels debates about over-diagnosis, as I explored in my blog on autism rates (https://aitoolforkids.in/are-autistic-kids-being-over-diagnosed-in-the-u-s-system/). Let’s dive into how autism’s symptoms mimic other disorders, why re-diagnoses occur, and what it means for kids.

The Autism Spectrum: Levels 1 and 2

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), per the DSM-5, involves challenges in social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors. Severity levels define support needs:

- Level 1: Requiring Support

Mild social difficulties (e.g., trouble with conversation flow) and some repetitive behaviors (e.g., rigid routines). Kids might seem “quirky” but function well, like a teen who avoids eye contact but excels in school. - Level 2: Requiring Substantial Support

More obvious social deficits (e.g., limited speech, odd responses) and frequent repetitive behaviors (e.g., hand-flapping). Kids need structured help, like a child with short sentences and intense interests.

Level 3 (severe) involves profound challenges, but Levels 1 and 2 are trickier to diagnose due to subtler symptoms that mimic other conditions. This overlap drives misdiagnoses, especially in the U.S., where autism rates hit 3.2% (CDC 2022).

Why the Mix-Up? Symptom Overlap Explained

Diagnosing autism isn’t a simple test—it’s complex, relying on tools like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2) and parent/teacher input.

For Levels 1 and 2, symptoms often look like other disorders, leading to errors. A 2016 study found up to 30% of initial autism diagnoses were later changed to conditions like these (Blumberg et al., 2016):

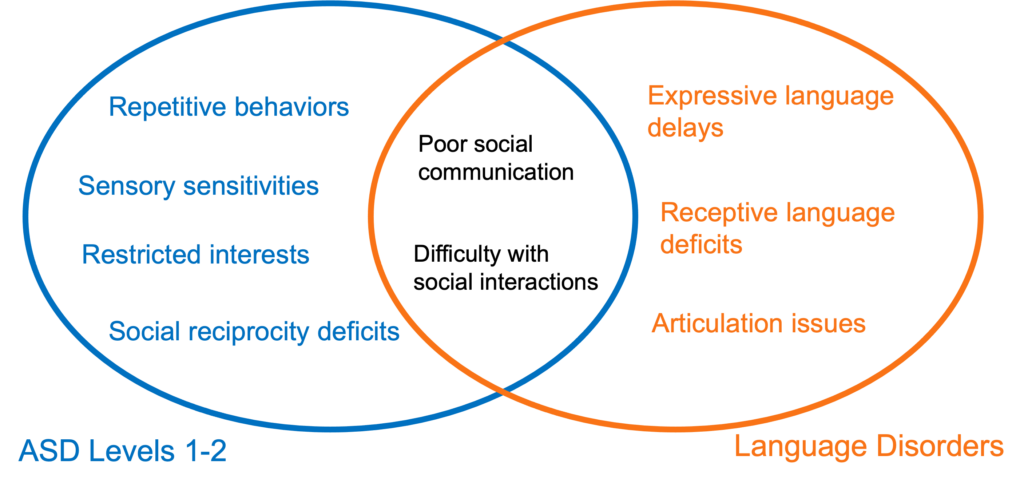

1. Language Disorders

ASD Levels 1-2

- Repetitive behaviors (e.g., hand-flapping, lining up toys, rigid routines).

- Sensory sensitivities (e.g., distress at loud noises, fascination with lights).

- Restricted interests (e.g., intense focus on trains).

- Social reciprocity deficits (e.g., trouble initiating play, per DSM-5).

Language Disorders

- Expressive language delays (e.g., difficulty forming sentences).

- Receptive language deficits (e.g., trouble understanding complex instructions).

- Articulation issues (e.g., unclear speech sounds).

Overlap Section

- Poor social communication (e.g., limited back-and-forth conversation, slow speech).

- Difficulty with social interactions (e.g., avoiding group chats due to language struggles).

- Example: A 5-year-old with short, halting speech might be misdiagnosed with Level 1 autism but later identified as having SLI after speech therapy improves social skills.

Why Confused: Both involve poor verbal interaction, but autism includes repetitive behaviors (e.g., toy lining), while SLI focuses on language alone.

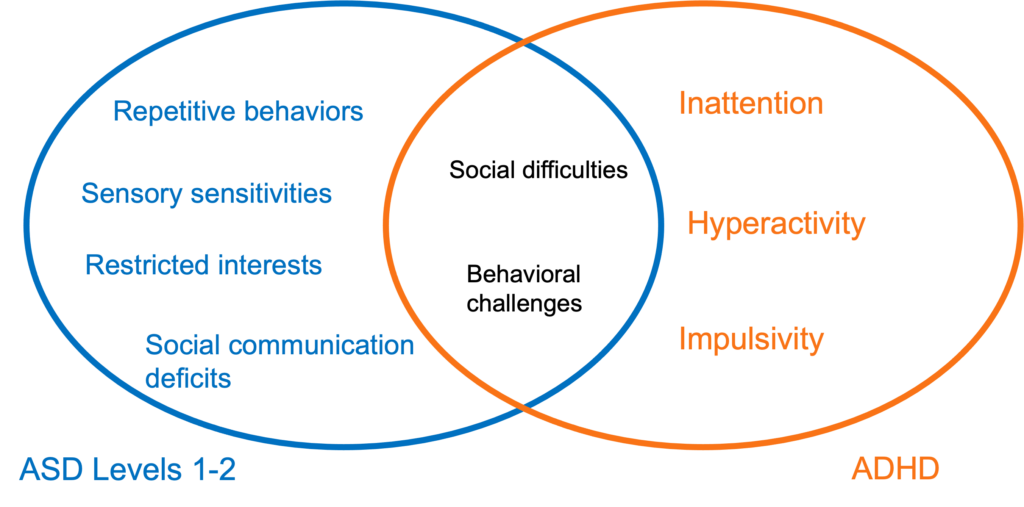

2. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

ASD Levels 1-2

- Repetitive behaviors (e.g., rocking, strict routines).

- Sensory issues (e.g., aversion to textures, per DSM-5).

- Restricted interests (e.g., obsessive focus on puzzles).

- Social communication deficits (e.g., missing nonverbal cues).

ADHD

- Inattention (e.g., forgetting tasks, losing focus in class).

- Hyperactivity (e.g., constant fidgeting, running excessively).

- Impulsivity (e.g., acting without thinking, interrupting others).

- No sensory sensitivities or restricted interests.

Overlap Section

- Social difficulties (e.g., interrupting conversations, missing social cues).

- Behavioral challenges (e.g., fidgeting mistaken for repetitive movements).

- Example: A 7-year-old who blurts out answers and loves routine might be diagnosed with Level 2 autism but later found to have ADHD after medication improves focus.

Why Confused: Social and behavioral overlaps blur lines, but autism’s core is social communication deficits, not ADHD’s attention focus.

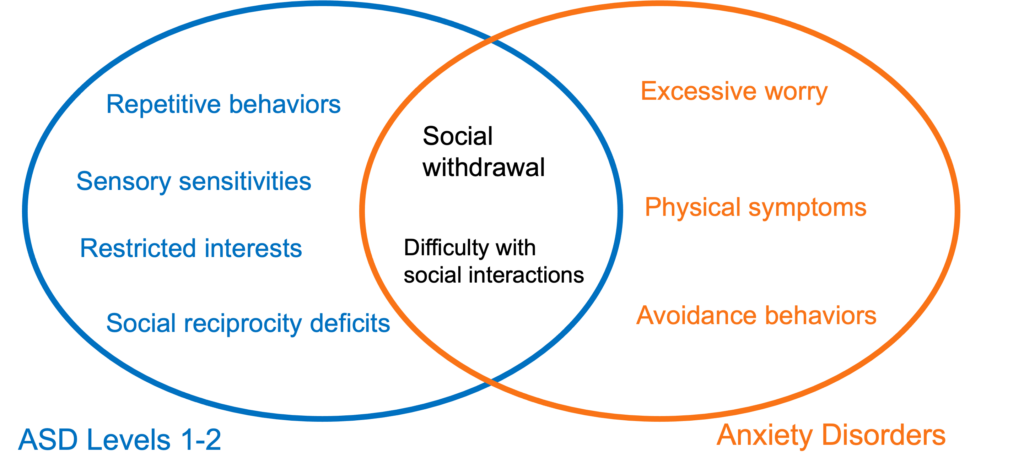

3. Anxiety Disorders

ASD Levels 1-2

- Repetitive behaviors (e.g., hand-flapping, ritualized greetings).

- Sensory sensitivities (e.g., distress at crowded places).

- Restricted interests (e.g., intense focus on dinosaurs).

- Social reciprocity issues (e.g., trouble maintaining friendships, per DSM-5).

Anxiety Disorders

- Excessive worry (e.g., fear of social judgment).

- Physical symptoms (e.g., racing heart, sweating in social settings).

- Avoidance behaviors (e.g., skipping school due to anxiety).

- No repetitive behaviors or sensory issues.

Overlap Section

- Social withdrawal (e.g., avoiding group activities, seeming shy).

- Difficulty with social interactions (e.g., hesitant speech in groups).

- Example: A teen who avoids parties and fidgets might be labeled Level 1 autistic but later diagnosed with social anxiety after therapy eases fears.

Why Confused: Both show social withdrawal, but anxiety lacks autism’s restricted interests or sensory issues.

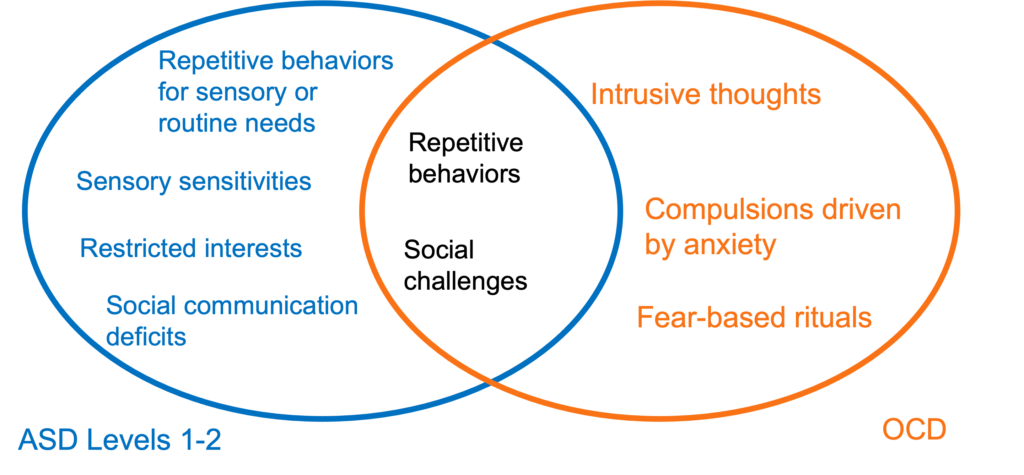

4. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

ASD Levels 1-2

- Sensory sensitivities (e.g., aversion to certain sounds).

- Restricted interests (e.g., fixation on maps).

- Social communication deficits (e.g., trouble with eye contact).

- Repetitive behaviors for sensory or routine needs (e.g., hand-flapping, per DSM-5).

OCD

- Intrusive thoughts (e.g., unwanted fears of harm).

- Compulsions driven by anxiety (e.g., checking locks repeatedly).

- Fear-based rituals (e.g., washing hands to avoid germs).

- No sensory issues or social communication deficits.

Overlap Section

- Repetitive behaviors (e.g., ritualized actions like arranging toys).

- Social challenges (e.g., seeming withdrawn due to focus on rituals).

- Example: A child obsessed with order might be diagnosed with Level 2 autism but later found to have OCD when rituals are revealed as fear-driven.

Why Confused: Repetitive behaviors overlap, but OCD involves intrusive thoughts, unlike autism’s sensory or routine-based patterns.

The Re-Diagnosis Reality

Why do 10-30% of Level 1 kids get re-diagnosed?

A 2016 Autism Research study found that milder cases are most prone to errors due to subjective assessments (Blumberg et al., 2016). Clinicians might misinterpret quirks—like shyness or intense hobbies—as autism, especially in the U.S., where screening is aggressive (3.2% prevalence vs. global 1%, Talantseva et al., 2023).

California’s 5.3% rate (CDC 2022) suggests over-diagnosis of mild cases, as I discussed in my over-diagnosis blog (link). Service incentives also play a role: autism diagnoses unlock therapies, tempting stretched labels.

Stereotypes Make It Worse

Stereotypes, like assuming autism means severe disability, add confusion, as I explored in my stereotypes blog (link). Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s April 2025 claim that autistic kids “never hold a job” focused on severe cases (Level 3), dismissing Level 1-2 kids who blend in. This mirrors my surprise when someone fluent reveals an autism diagnosis. Movie tropes (e.g., savants in Rain Man) expect extreme traits, making mild cases seem “not autistic,” fueling skepticism about diagnoses.

Implications for Kids

Misdiagnosis hurts.

A child labeled autistic might get intense behavioral therapy instead of speech help for a language disorder. It can also affect self-esteem, as kids internalize a “problem” label.

Over-diagnosis strains resources, diverting support from severe cases (Level 3), per a 2019 Autism editorial. Clearer diagnoses help kids get the right support.

Educate parents about overlaps—shyness isn’t always autism. Have you seen kids misdiagnosed?

References

Blumberg, S. J., Zablotsky, B., Avila, R. M., Colpe, L. J., Pringle, B. A., & Kogan, M. D. (2016). Diagnosis lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 20(7), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315607724

Greenlee, J. L., Mosley, A. S., Shui, A. M., Veenstra-VanderWeele, J., & Gotham, K. O. (2016). Medical and Behavioral Correlates of Depression History in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 137 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S105–S114. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851I

Talantseva, O. I., Romanova, R. S., Shurdova, E. M., Dolgorukova, T. A., Sologub, P. S., Titova, O. S., Kleeva, D. F., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2023). The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1071181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1071181

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696