1,380 words, 7 minutes read time.

Posts in Autism Series

- Are Autistic Kids Being Over-diagnosed in the U.S. System? (This post)

- Could Rising Autism Rates Spark an Epidemic Among Kids?

- Stereotypes of Autistic Kids: Beyond the Myths

- Is It Autism? Symptom Overlap in Mild Cases

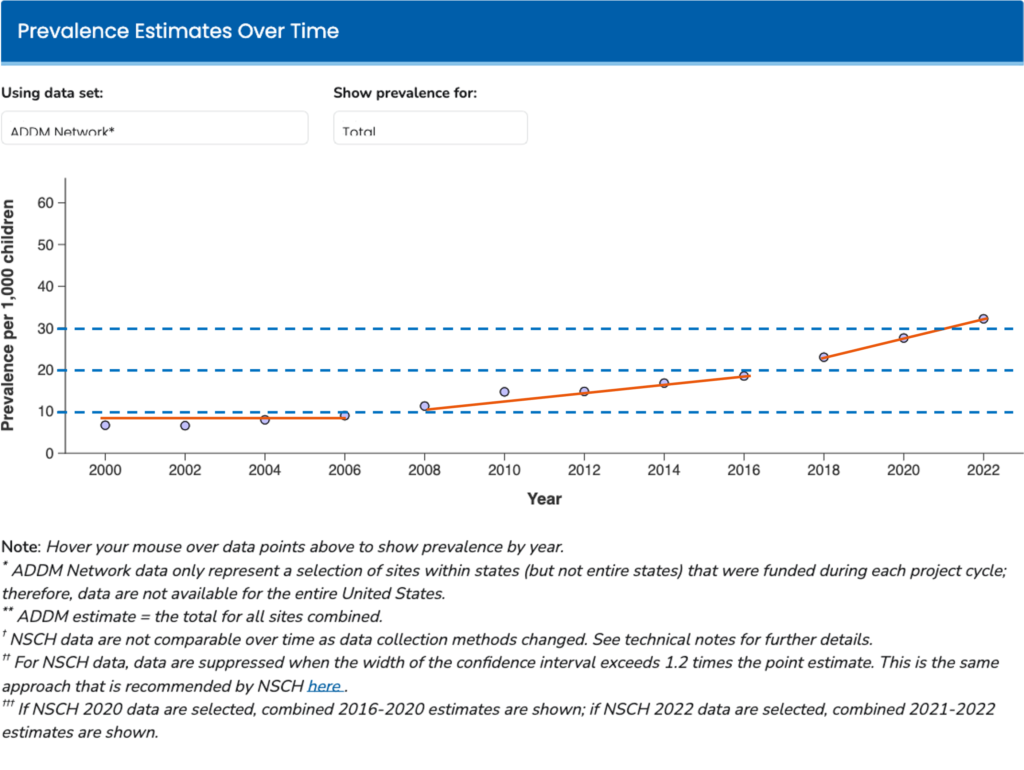

Let's first take a look at the chart of "Autism Prevalence Estimates Over Time" (among 8-year-olds) from CDC.

Here are facts I can read from the chart:

1. In 2000, 1 in 150 kids (0.67%) in the U.S. was diagnosed with autism;

2. By 2022, that number goes up to 1 in 31 (3.23%);

3. From 2000 to 2006, the Autism rate remains stable around 1 in 150 kids in the U.S. (0.67%);

4. From 2008 to 2016, the rate gains 1% in 8 years;

5. From 2018 to 2022, the rate gains another 1% in 4 years.

Source: downloaded from CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/autism-data-visualization-tool.html). I added blue dotted lines and orange solid lines to segment the trends.

Are we facing an autism epidemic, or is our system diagnosing too many kids as autistic?

Better autism screening helps many kids get support, but over-diagnosis may boost numbers.

This blog explores whether we’re casting too wide a net, driven by broad criteria, service incentives, and cultural pressures—while still respecting the reality of autism and the families navigating it.

Let’s be clear: autism is real, and every child deserves the right support. But as someone who’s watched diagnosis rates climb, I wonder if our system is too quick to label kids, especially kids with milder symptoms.

Here’s a closer look at why autism diagnoses are going up, whether over-diagnosis is a problem, and how we can find balance.

Understanding Autism and Its Diagnosis

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition affecting how people communicate, interact, and behave.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), autism involves two core challenges:

- deficits in social communication (like trouble with conversation or eye contact) and

- restricted, repetitive behaviors (like hand-flapping or intense interests).

It’s a spectrum, meaning one child might be nonverbal and need lifelong care, while another might excel academically but struggle with social cues.

Diagnosing autism isn’t like a blood test—it’s complex. Clinicians use tools like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2), observe behaviors, and gather input from parents and teachers.

But interpreting mild symptoms, especially in young kids, can be subjective, because complex systems usually come with big uncertainty. A child who’s shy or loves lining up toys might raise flags, but is it always autism?

The numbers tell a story. The CDC’s 2022 report found autism prevalence at 3.23% (1 in 31) among 8-year-olds, up from 0.67% (1 in 150) in 2000. Better screening, broader diagnostic criteria since the DSM-5’s 2013 release, and growing awareness partly explain this rise. But are we catching every case—or overreaching?

Evidence of Potential Over-diagnosis

1. DSM-5 includes more milder cases

Unlike its predecessor, which split autism into subtypes like Asperger’s, the DSM-5 uses a single ASD diagnosis that includes milder cases. A 2014 study in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders estimated this change boosted diagnoses by 10-20%. A kid with social awkwardness or a passion for trains might now be labeled autistic, even if they thrive in school. This broad net raises questions about where we draw the line.

2. Diagnosis incentives: more diagnosis leads to more funding support

Then there’s the role of incentives. In the U.S., an autism diagnosis unlocks critical resources: Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), behavioral therapy, or state-funded support, especially in places like California.

A 2016 Pediatrics study (Greenlee et al., 2016) noted that some families and clinicians pursue diagnoses to access these services, even for ambiguous cases. Historically, California’s autism increase from 1992-2005 was partly due to reclassifying intellectual disability as autism for funding—about 25% of the rise, per studies. This suggests “diagnostic substitution” may still inflate numbers.

Regional differences of prevalence of ASD

1. USA, 1.12%

2. Sweden, 0.09%

3. Denmark, 0.73%

4. China, 0.42%

5. France, 0.32%

6. Taiwan, 0.11%

(Data used to 2020, Talantseva et al., 2023)

Regional differences add fuel. The CDC’s 2022 data shows California’s prevalence at 1 in 19, while Laredo, Texas, lags at 1 in 103. California’s robust screening, specialist access, and detailed record-keeping catch more cases, especially mild ones. But in Laredo, limited resources likely mean under-diagnosis. Could California’s high rate reflect over-identification?

California is an outlier in terms of ASD rate (source: CDC)

1. California (2018): 3.9%

2. California (2020): 4.5%

3. California (2022): 5.3%

while, 1 in 100 children (1%) are diagnosed with autism across the world (Zeidan et et., 2022).

3. Symptom overlap with others

Autism is a big bucket, when kids suffer from ADHD, anxiety or language disorders, kids are very likely to be diagnosed to be autism.

Autism also overlaps with conditions like ADHD, anxiety, or language disorders. A 2016 Autism Research study (Blumberg et al., 2016) found that up to 30% of kids initially diagnosed with autism were later re-diagnosed with something else. A child with ADHD’s impulsivity might be mistaken for autism’s social deficits, especially if clinicians aren’t thorough.

4. Healthcare system in the US plays

Finally, the U.S.’s medicalized culture plays a part. Globally, autism prevalence averages 1%, per a 2022 Frontiers in Psychiatry review (Talantseva et al., 2023), but the U.S. hits 3.2%. Countries like France, using stricter ICD-10 criteria, report lower rates (~0.5-1%). Our aggressive screening and inclusive DSM-5 may diagnose kids other countries miss—or we might be over-diagnosing. (Talantseva et al., 2023)

Implications of Over-diagnosis

Over-diagnosis has real consequences.

For kids, an unnecessary label can affect self-esteem or lead to therapies that don’t fit—like intense behavioral programs for a child with anxiety, not autism. For society, it strains resources. A 2019 Autism editorial warned that over-diagnosing mild cases could divert support from kids with severe needs (Level 3). Public perception also suffers when figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (April 2025) call autism a “preventable epidemic,” fueling stigma and fear.

This isn’t unique to autism. ADHD and anxiety diagnoses have surged, too, suggesting a broader U.S. tendency to medicalize differences. Our fee-for-service healthcare and push for school accommodations may amplify this, unlike countries with less diagnosis-driven systems.

The Flip Side: Under-diagnosis and the Need for Balance

Over-diagnosis isn’t the whole story. Under-diagnosis remains a problem, especially for girls, minorities, and underserved areas like Laredo.

A 2020 Autism Research study showed that girls and minority kids are often missed because their symptoms (e.g., internalizing behaviors) don’t match stereotypes. In places with limited healthcare, kids may never get evaluated.

Diagnosis also brings benefits. Early intervention—like speech therapy by age 3—can transform outcomes for autistic kids. Even borderline diagnoses can secure support for related challenges, which is why some flexibility makes sense. The trick is balance: catching true cases without labeling kids who don’t need it.

Conspiracy Theory

Some whisper that autism diagnoses are being inflated by a hidden agenda: Big Pharma and healthcare giants profit from every new case. With the U.S. autism rate at 3.2%—far above the global 1% (Talantseva et al., 2023)—and California hitting 5.3% (CDC, 2022), could powerful interests be pushing clinicians to over-diagnose?

Each diagnosis triggers costly therapies and medications, filling corporate pockets. Stricter countries like France (0.5%) avoid this trap, but America’s loose DSM-5 and screening frenzy keep the cycle spinning. Is it about helping kids—or fueling a healthcare goldmine?

Do you think autism is over-diagnosed where you live? Share your thoughts or experiences below!

References

Blumberg, S. J., Zablotsky, B., Avila, R. M., Colpe, L. J., Pringle, B. A., & Kogan, M. D. (2016). Diagnosis lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 20(7), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315607724

Greenlee, J. L., Mosley, A. S., Shui, A. M., Veenstra-VanderWeele, J., & Gotham, K. O. (2016). Medical and Behavioral Correlates of Depression History in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 137 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S105–S114. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851I

Talantseva, O. I., Romanova, R. S., Shurdova, E. M., Dolgorukova, T. A., Sologub, P. S., Titova, O. S., Kleeva, D. F., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2023). The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1071181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1071181

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696

Pingback: Could Rising Autism Rates Spark an Epidemic Among Kids?

Pingback: Stereotypes of Autistic Kids: Beyond the Myths

Pingback: Is It Autism? Symptom Overlap in Mild Cases -